A Short History of Ballston Spa, New York

copyright 2007-2008 Timothy Starr

The Town of Milton encompasses nearly all of the Village of Ballston Spa as well as most of the other villages served by the railroad. It had its beginnings in 1708 as part of the Kayaderosseras Patent. The boundaries of the town form a nearly perfect square in the center of Saratoga County, comprising 20,935 acres. The roads and trails used by early settlers were the footpaths used by the Mohawk Indian tribe to hunt and fish in the summer months. In 1771, so the story goes, some surveyors hired to calculate the boundaries of the Kayaderosseras patent were busily engaged in their duties when they spied a bubbling spring near the Kaydeross Creek. Little did they realize at the time that they just discovered the first mineral spring in America, to become known as the Iron Railing Spring (for the iron railing that was installed around it to keep out animals. Its supposed healing powers soon attracted tourists from around the country. The waters of Ballston Spa were part of what was known as the “Hudson River slate,” encompassing the cities of Albany, Argyle, Saratoga, and Ballston. Colonel Humphries, an officer of the Revolution, reported that the springs along the Kaydeross were great favorites of the soldiers, and that “the waters were in large measure substituted in the place of intoxicants, and less drunkenness existed” when the troops were in the area. For years afterward, though tourists would visit, no permanent settlement or improvements were made. The turning point came in 1787 when Benajah Douglas arrived and built a spacious log cabin near the spring. He then purchased 100 acres of land and erected a small hotel for visitors during their brief visits. This bit of comfort prompted more tourists to come to the area who may have balked at spending the night in the wilderness. In 1795, Joshua Aldridge purchased the hotel, enlarged it, and named it “Aldridge House,” charging $8 per week for guests. Today the building is known as Brookside (home to a museum).

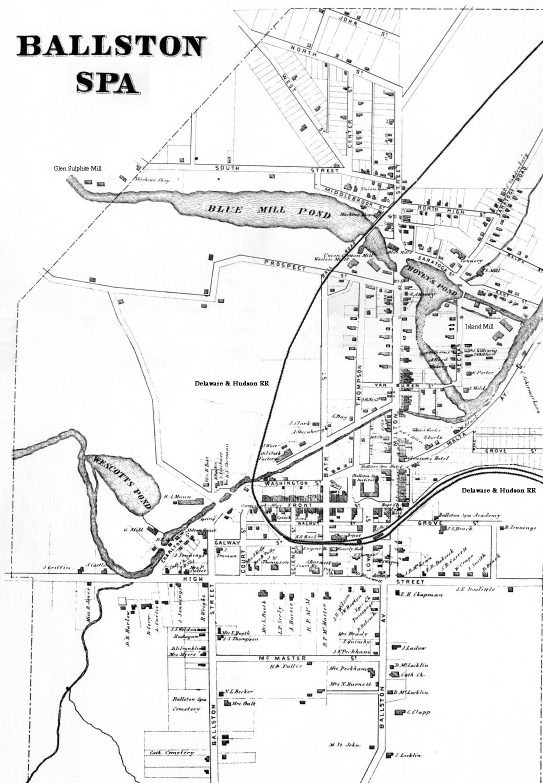

For about 30 years, Low almost single-handedly guided the development of the village. He subdivided his extensive land holdings into small parcels and laid out several streets in a grid-like pattern, based on Front Street. In 1823 he deeded a lot to Saratoga County for the construction of the County Clerk’s office, thereby guaranteeing that Ballston Spa would remain the county seat of government despite the rise of Saratoga Springs in size and importance. Other springs were discovered near the original mineral spring, all having slightly different tastes and quality. A scientific writer stated “the original spring issues from a bed of stiff blue clay and gravel, which lies near a stratum of slate nearly on a level with the brook or rivulet which runs through the town.” When the Artesian Litha Spring was discovered as a ditch was being dug near Saratoga Avenue, it first gushed oil, supposedly superior to that of the Pennsylvania oil region. However, some time later the spring began spouting water every third day until it was tubed. Another early spring was the Glen Spring, located a short distance up the Kaydeross Creek where the Glen Sulphite mill would eventually be built. For years, fashionable guests would take a boat ride up the creek to taste the waters of this spring. Even the spirits seemed to be attracted to Ballston. Dr. Barron, a physician from Massachusetts, arrived in the village and said he was directed by the spirits to come to Ballston and purchase a certain piece of land south of the Red Mill (near Brookside), on which would be found a mineral fountain whose water would be “for the healing of nations.” He went on to purchase some land for $1,000 and searched for the spring for several months without success. Fifteen years later, however, Samuel Hide of Malta Avenue claimed that Benjamin Franklin had communicated to him in a séance to drill at a particular spot on his farm. When he did so, water began spouting over 50 feet in the air, and became known as the Franklin Spring. Although springs had been discovered in Saratoga, they were not as well-known as those of Ballston for some time. A visitor to upstate New York in 1802 described Saratoga as “a small village with pretty accommodations near the Great Rock Spring; but the principle resort is at Ballston.” After the construction of its grand hotels, upper class tourists flocked to the village. Visiting in 1807, Washington Irving noted the increasing presence of women, who came, not so much for health and good company as to “exhibit themselves and their finery; to excite admiration and envy.” He observed that “a sober citizen’s wife will sometimes starve her family for a whole season” in order to visit the springs in style. Becoming a center of fashion, as well as being situated with easy access from New York City via the Hudson River, were crucial factors to the success of Ballston Spa over other early spas located near Albany. In all, 16 springs were drilled, attracting more and more wealthy businessmen as well as tourists. Some of these businessmen elected to remain in the area past the summer season, which would bode well for the village in the future when industrial pursuits would take on growing importance in the 1840s. As the forests all around the springs were cleared and other hotels were added, the small settlement gradually grew to become a thriving village, with stores, schools, churches, shops, and boarding houses. The mineral waters were touted as being especially effective for diabetes, rheumatism, heart disease, and gout. Local physicians and practitioners routinely used the water for disease treatment. Ballston Spa’s medicinal waters and hotels placed it near the top of the list of summer destinations in the United States, and earned it the nickname “America’s First Watering Place.” The prosperity proved to be short-lived. When spring water was discovered in Saratoga, a man named John Clarke had the foresight to bottle the water from Congress Spring and sell it across the country. The fame of the bottled water spread and soon caused the popularity of Ballston Spa to be eclipsed by Saratoga Springs. To make matters worse, several of the springs in Ballston Spa that showed so much promise of longevity failed. One account says that in an attempt to dig up and re-tube them to increase their flow, several veins were lost. Joshua Aldridge reportedly remarked to the workers who were digging up the original spring, “My house is full of boarders; you might as well burn it down and destroy my business that way as to tamper with that spring.” Another theory was that the mills along the creek, which were to save the village and town from destitution, may have had a part in the failure of the springs. Benjamin Silliman, a professor of chemistry at Yale College, wrote that the dams that were constructed along the creek for the mills had caused the fresh water to find its way through seams in the shale rocks and mingle with the sources of the mineral water, thus diluting their medicinal value. Even if the springs had not failed, a region that derives its income solely on tourism is subject to the economic conditions of the day as well as seasonal factors. Since the tourism season generally ended on September 1, there was very little activity in the village for over half of each year. If Milton and Ballston Spa only had the springs to ensure prosperity, the area would have long ago lost a significant part of its population (such as what occurred in Milton Center after the tannery burned down and was rebuilt elsewhere). Fortunately, the town had the Kaydeross Creek to fall back on. The stream flows from the north in a southeasterly course, falling rapidly in elevation. Although the Kaydeross doesn’t seem like it could provide enough energy to power so many operations, it was reportedly much larger in the past than it is today. Several mills were erected by the early 1800s, mainly near Ballston Spa and Rock City Falls. General James Gordon built a mill in Milton Center around 1786. He also erected the first sawmill in Middle Grove (in the Town of Greenfield, just north of Rock City Falls). By 1813, there were eight grain mills, four carding mills, a woolen factory, and two iron forge factories. Only Corinth had more sawmills than Milton in Saratoga County. It is believed that around this time, the area was known as Mill Town, eventually shortened to Milton. Hezekiah Middlebrook built the first dam across the Kaydeross, and in 1830 erected a mill nearby later known as Blue Mill. Jonathan Beach and Harvey Chapman built a woolen mill at the site of Island Mill in Ballston Spa. That same year, Seth Rugg established a large spinning wheel factory in Milton Center, later to become a tannery. But the town’s industry was not robust enough to support its own railroad until several entrepreneurs moved to the area in the middle of the century, and began to build the large mills that helped make the town prosperous once again. Best known among these industrialists was George West. West was not the only entrepreneur who established large industries in the village. In 1868, Horace Medbery and Henry Mann purchased the Blue Mill and greatly expanded it. The mill then became known as the Glen Paper Collar Company, producing paper collars. For a number of years it was the largest manufacturer of its kind in the United States. Perhaps the most popular employer of the time was Isaiah Blood of the Ballston Axe & Scythe Works. By the late 1890s, the Town of Milton was experiencing the greatest extent of its manufacturing enterprises. The Saratoga Guide Illustrated described it as a “manufacturing town devoted largely to the manufacturing of paper bags, envelopes, leather, and axes.” This made the town, as well as the village of Ballston Spa, almost entirely composed of middle- to upper-class families, with nearly 100 percent employment. It is safe to say that the industrial development of the Kaydeross Creek saved the village of Ballston Spa and the Town of Milton from possible obscurity. It certainly would not have been the first time in American history for a village or town to become deserted once the engine driving the economy disappeared. Fortunately, the paper mills, Bull’s Head tannery, Uline’s foundry, and others kept the area prosperous until the advent of the automobile and the state highway system permitted residents to remain in Milton and commute to the cities for employment.

[Home] |

Several more

entrepreneurs followed Douglas to Ballston Spa, including Nicholas Low, formerly

a merchant in New York City. In 1803 he built a large resort hotel on

present-day Front Street, called the Sans Souci, which was built from plans

based on the palace Versailles furnished by Andrew Berger. It was the largest

hotel in the country at the time, an indication of the village’s standing as a

major tourist destination after just a few short years. The Sans Souci was the

entertainment destination of distinguished visitors from all over the world –

senators, governors, judges, and even presidents. Joseph Bonaparte (ex-king of

Spain) was visiting there in 1827 when he received a letter that announced the

death of his brother Napoleon. Other visitors included Daniel Webster, Henry

Clay, Martin Van Buren, J. Fennimore Cooper, Andrew Jackson, and Washington

Irving. Jacob Cohen of South Carolina wrote, “There is no place like Ballston,

and no hotel like the Sans Souci, though I have visited all the famous watering

places on the continent.”

Several more

entrepreneurs followed Douglas to Ballston Spa, including Nicholas Low, formerly

a merchant in New York City. In 1803 he built a large resort hotel on

present-day Front Street, called the Sans Souci, which was built from plans

based on the palace Versailles furnished by Andrew Berger. It was the largest

hotel in the country at the time, an indication of the village’s standing as a

major tourist destination after just a few short years. The Sans Souci was the

entertainment destination of distinguished visitors from all over the world –

senators, governors, judges, and even presidents. Joseph Bonaparte (ex-king of

Spain) was visiting there in 1827 when he received a letter that announced the

death of his brother Napoleon. Other visitors included Daniel Webster, Henry

Clay, Martin Van Buren, J. Fennimore Cooper, Andrew Jackson, and Washington

Irving. Jacob Cohen of South Carolina wrote, “There is no place like Ballston,

and no hotel like the Sans Souci, though I have visited all the famous watering

places on the continent.”